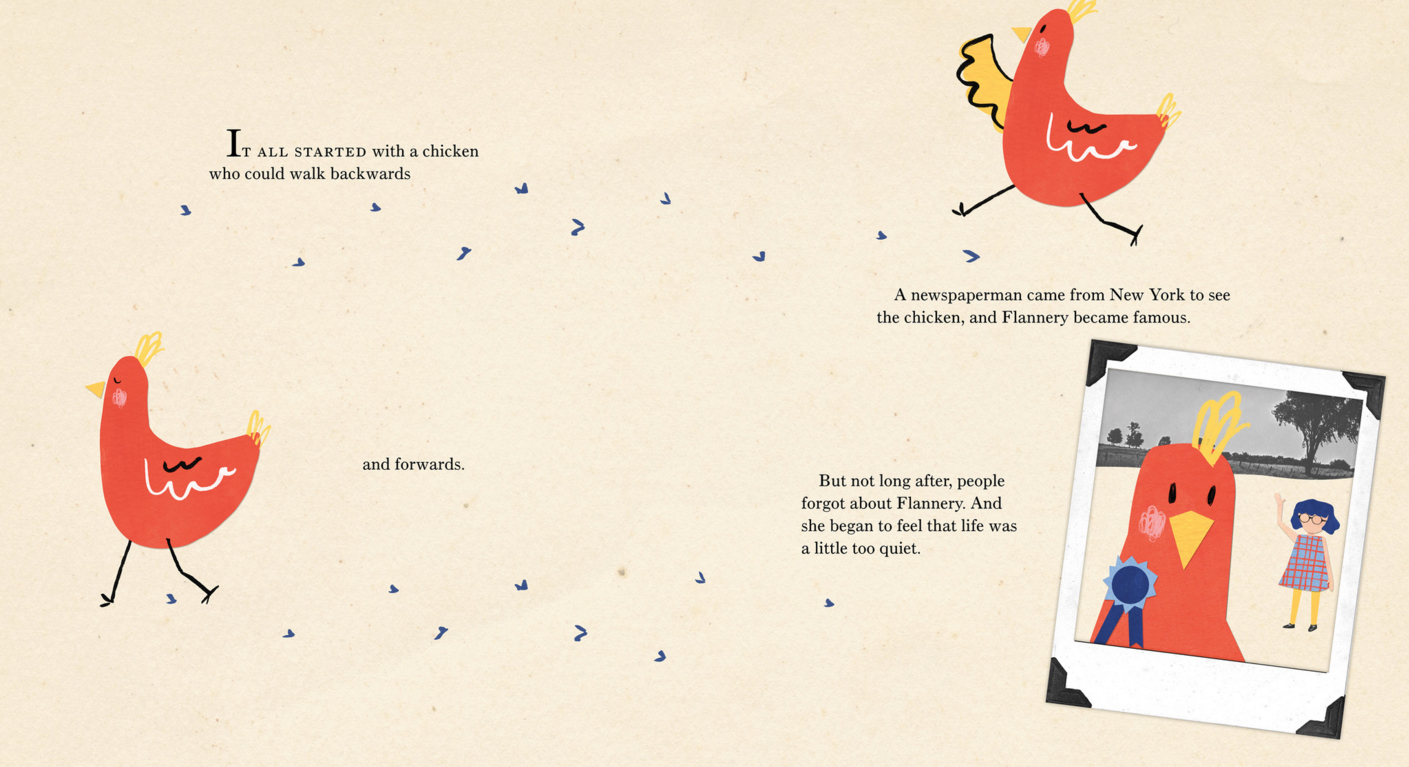

The King of Birds is a colorful, playful homage to Flannery O’Connor and her love of birds written by Acree Graham Macam and illustrated by Natalie Nelson—who also happen to be close friends. Loosely based on an essay of the same title, The King of Birds imagines how Flannery, as a child, might have gone about collecting her assortment of birds, and we follow along as she solves the problem of getting her prize peacock to show his magnificent fan. It’s a wonderful way to introduce young readers to Flannery O’Connor and captures her quirkiness perfectly. We think her peacocks would approve.

Groundwood Books, 2016

You were friends before you were collaborators. Was writing a book together something you planned to do or did it just grow out of your friendship?

Natalie: The book definitely grew out of our friendship. We did collaborate on a few smaller projects together before the idea for the book came along though, and we found out how much we enjoyed working together through those early collaborations.

Acree: The collaboration between us started during a time when I had recently quit my job at an ad agency, and Natalie had left portfolio school. We both had some time on our hands and were looking for meaningful work to do. We would get coffee just about every Friday and talk about projects together.

Since a picture book is both a written story and art, how did you start the process after you settled on an idea? With the illustrations? The writing? Both at the same time?

N: The idea for the book originated after I read O'Connor's essay, "The King of the Birds," and visited O'Connor's home, Andalusia, around the same time. When I came back from my trip, I started furiously sketching and jotting down ideas for a story loosely inspired by the essay. I shared my excitement with Acree, and also my trepidation at writing it myself, and she offered to work on writing the story. I was thrilled! If I remember correctly, she came back to me with a rough draft of the story, and then I would do some drawings of a few of the scenes, and then she'd revise the story, and we'd go back and forth like that for a while. Eventually we were both really pleased with the story, and I sketched out the entire book, and then we started submitting to publishers.

A: I knew nothing about picture books at the time, but I loved the idea of a children's story based on a great southern author. I remember going home and laying out pages of printer paper as the spreads for the book. I did some really elementary drawings on some of the pages just to help myself remember that the pictures would be telling half of the story. Then I took the bones of the story that Natalie had sent over and started writing the manuscript. There was a lot of back and forth between us to chisel it into its current shape. The writing would influence the pictures, which would impact the next draft, and so on.

Flannery O’Connor probably wouldn’t be most readers’ pick as the main character in a picture book. Why did you choose to tell a story about Flannery?

N: The essay that inspired our story is a bit of a departure from the Flannery most people know. It's still full of her incredibly dry wit, but it's lighter and more playful than most of her other writing. You get a glimpse of her as just a woman who loves peacocks, and even though they can be difficult pets with odd and bewildering behaviors, she loves them all the more for it. This Flannery seemed like the perfect one to introduce to young children.

A: I used to just sort of ignore picture books, because I thought of them as boring stories about animals with a trite "moral" at the end. So Natalie's idea of a children's book about someone with a very non-Kindergarten-teacher voice (O'Connor) ripped the ceiling off my idea of what children's literature could be, in a way that was very exciting. I'm not sure I would have considered writing a children's book if it wasn't about O'Connor.

Flannery’s short stories are often described as grotesque, haunting, and “the most powerful and disturbing fiction written this century.” Since Flannery originally wrote for adults, was it difficult translating her personality and her stories into a book for children?

N: The fun thing about this story is it is just as much (if not more) about The Peacock as it is about Flannery. We wanted to tell a story about The Peacock in a way that Flannery might have told it to young children. It is a window into an imagined life of Flannery and one of her stubborn birds, drawn from several factual details, that we hope will delight both fans of Flannery and Flannery-illiterates.

A: I think O'Connor's stories are dark because they tell the truth about the American South that she experienced. She liked to tell it like it is, and while her non-fiction lacks the grotesque imagery of her stories, it has her signature dry wit. She could have written about a dustbin, and I'm sure we would all crack a smile reading it. So as I read her essay "The King of the Birds" over and over, I just kind of got her voice in my head. Then I approached the children's story from that lens.

Acree, writing the story of a picture book must be quite different from writing longer-form stories. In general, how do you decide what the story in a picture book should sound like?

A: Since picture books are often read out loud, I spent a lot of time reading the manuscript to myself and hearing what it sounded like. You don't want to give the reader too many words to stumble over, or a cheesy line that they feel gross saying. I also had to remember to leave room for the pictures. You don't want a page where you've got an illustration of a duck eating strawberries and the words are saying, "The duck ate strawberries." So I spent a lot of time paring back the manuscript until there were no more words I could cut. That also involved quite a bit of collaboration between Natalie and me, trying to decide (and sometimes arguing about, pleasantly) that dance between the words and the pictures.

Natalie, your style is a collage of real photos, colorful paper, and hand drawn elements. How did you develop your style? Did you “just know” when you found it?

N: I learned to love mixing media way back in high school, so in some ways it has always felt natural to me to use a variety of materials to complete my illustrations. I had been making editorial illustrations for a few years when I started working on this book, and had grown very used to adding in bits of found photography to all of my work. I also made many of the original drawings of the birds out of cut paper which I really loved, so in the end I just found a way to combine all my favorite ways of working into the final art.

For any young readers who want to write and/or illustrate their own books, what advice would you give to them?

N: Write and draw as much as you can, put all your ideas on paper, even the really bad ones, and don't give up!

A: Don't worry about what you think books are supposed to be. Write what makes sense to you, and allow it to ask more questions than it answers.

What have been some of your favorite picture books that you’ve read this year? (Who are some of your favorite women creating picture books?)

N: Oh I love this question. My all time favorite author/illustrator is Maira Kalman, and I've been loving a series of books she's put out over the last couple years in collaboration with Daniel Handler, aka Lemony Snicket. Laurel Snyder, a fellow Atlantan, writes really wonderful picture books and books for older children. My friend Aimee Sicuro illustrates beautiful books, including one called I Feel Teal that is coming out this summer. Some other favorite women illustrators of mine are Dasha Tolstikova, Isabelle Arsenault, Carson Ellis, and Paloma Valdivia.

A: I've been revisiting a lot of Margaret Wise Brown books this year. Everyone knows Goodnight Moon, but there's also a really lovely and weird book called The Dead Bird that was recently re-illustrated. It's this simple but beautiful exploration of children encountering death. Her book North, South, East, West was also recently re-illustrated. I read it in the middle of a bookstore and cried right there in the children's section. And Runaway Bunny is a heartbreaking story that I didn't understand until I read it as an adult. As far as living authors go, Carson Ellis's Du Iz Tak? is great—I think your readers would like her made-up language. It's kind of like the product names at IKEA—you don't know the words, but you intuitively understand them. Then a few non-fiction books I've enjoyed recently are Voice of Freedom (about civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer) by Carole Boston Weatherford, I Dissent (about Ruth Bader Ginsburg) by Debbie Levy, and Swan (about a Russian ballerina) by Laurel Snyder.

Is there anything either of you are working on now?

N: I illustrated a book called A Storytelling of Ravens that comes out this May. I'm beginning to work on a very exciting picture book about an important woman who helped engineer the Brooklyn Bridge. That one will publish Spring 2019. And Acree and I are trying to work on another collaboration too. Wish us luck!

A: I have a manuscript in the hands of an agent that I'm working on selling. Keep your fingers crossed for that and hopefully more Acree/Natalie collaborations in the future.

Photo Credit: Andrew Thomas Lee

About Acree

Acree Graham Macam is the author of The King of the Birds as well as a writer and strategist at a messaging consulting firm. Previously an independent copywriter, she graduated Phi Beta Kappa with Highest Honors from Emory University's creative writing program, where she was awarded the Louis Sudler Prize in the Arts for her writing. She lives in Atlanta with her husband.

Website | Instagram | Twitter

Photo Courtesy of the Author